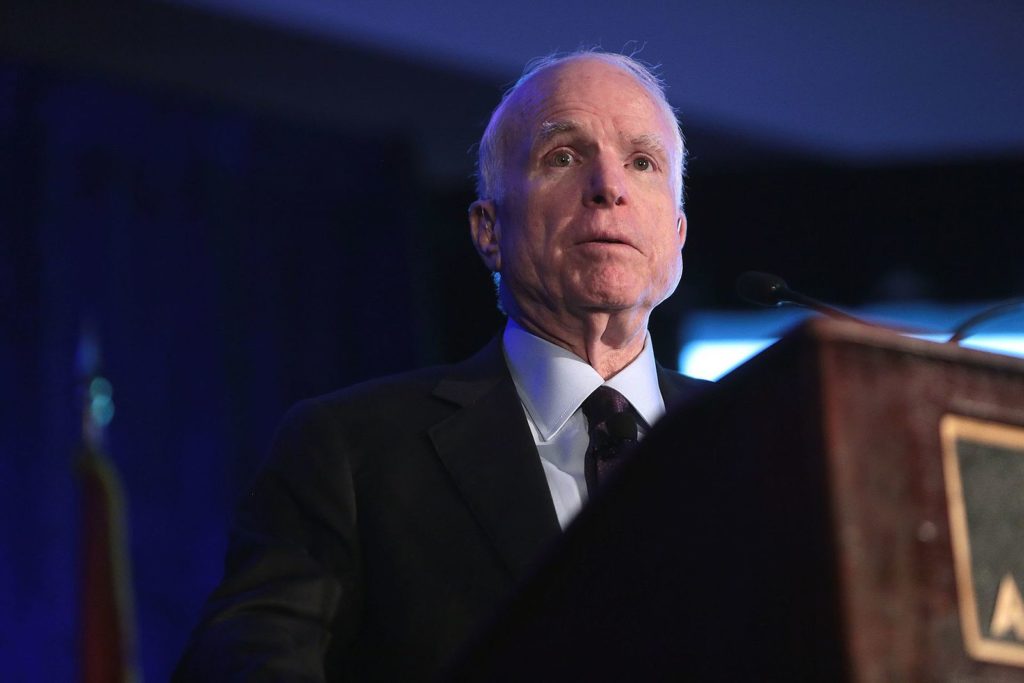

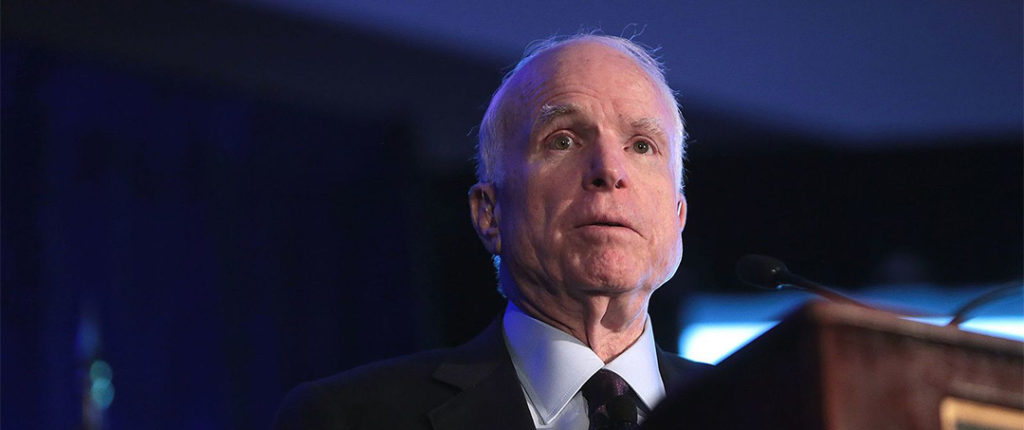

Graham Vyse of the New Republic offers important lessons for managing the media in a story headlined, “How the Washington Press Fell in Love with John McCain.”

Setting aside my objections to the headline, I recommend the essay to reporters and public relations professionals struggling to create best practices for the 21st century – when media, once the domain of so-called Gatekeepers, is now a hyper-democratized, 24-7, social ecosystem that infuses power to billions of people connected to the internet.

Vyse’s subhead gets to the heart of the McCain matter: “He gave reporters unprecedented access to his ‘Straight Talk Express’ presidential campaign in 2000, and it has paid off ever since.” I rode McCain’s bus for days at a time as an Associated Press reporter, and while I never fell in love with him, I fell in love with his approach to the media. Those lessons are more relevant today than in 2000.

Access: The Arizona senator sat in a captain’s chair aboard his bus and answered reporters’ questions for hours at a time. I can remember running out of things to ask McCain. Journalists who covered McCain quickly learned what made him tick, how he processed decisions, and why he conducted himself the way he did (for better and worse). In short, we had context. Public relations professionals often complain about how little context reporters bring to their stories. They expect reporters to accept pre-packaged context. Lesson: Give reporters the access they need to witness the context and they’re more likely to believe it.

Authenticity: McCain admitted mistakes. He chastised reporters. He teased reporters. He praised reporters. He once called me “a stupid fool,” and then made a pretty good case for the claim. It was refreshing to cover somebody who didn’t hide behind his PR team and talking points, who spoke in full and frank paragraphs. While most reporters, including me, remained skeptical about McCain, they trusted him more than most politicians. Lesson: Authenticity doesn’t guarantee positive coverage, but it can earn your client a rare and valuable privilege: the benefit of the doubt.

Vulnerability: One day in New Hampshire, when the rest of the press corps had left the bus to pre-position for McCain’s speech, I stayed behind to file my story. It was quiet – just me, the candidate, and an aide. The silence jarred me, so I looked up from my laptop to see the aide combing McCain’s hair. It hit me: McCain couldn’t raise his arms above his shoulders. He couldn’t comb his hair. The torture he suffered as a Vietnam War POW had robbed him of his mobility. Then, I watched McCain contort himself, and wincing, as the aide pulled a sweater over his broken shoulders. That moment made McCain human to me. It’s easy for reporters to take a cheap shot at a title – the Candidate … the President … the CEO. It’s hard to be unfair to somebody you’ve gotten to know, who you’ve broken bread with, who’s been authentic and vulnerable in your presence. Lesson: Humanize your client to immunize your client.

Good copy: One Vyse takeaway is as simple as it is powerful. “McCain understands something elemental about journalists: They love to hear good stories, and they love to tell good stories. This might seem obvious, but few politicians, in 2000 or 2018, have shown a willingness to give reporters the necessary access for such stories—nor do many politicians have personal stories as dramatic as McCain’s. Thus, most campaigns and congressional offices these days are more tightly scripted than a prime-time crime procedural on CBS.” The lesson: Don’t waste reporters’ time with bad story pitches and bad storytelling.

In the 18 years since that campaign, the media business has been disrupted and democratized. In 2000, McCain and his public relations team were totally reliant on the coverage of a few dozen reporters and their editors – fewer than 100 journalists so powerful that they were called Gatekeepers. The internet killed the Gatekeepers, diluting and distributing their power across millions of electronic platforms and onto the fingertips of billions of people.

Which is why I believe McCain was ahead of his time. His communications style is better suited for today, when people have lost trust in the leadership of social institutions, especially politics, government, big business and perhaps most of all: The Media.

The radical connectivity of the internet – the new media, more social and personal than ever – gives 21st century leaders and their PR consultants the opportunity to rebuild trust with access, authenticity, and vulnerability – and through vibrant storytelling.

Vyse quoted me in his essay about politics, but I believe this final thought applies to any PR client.

“I really think McCain created a template for modern campaign communications that unfortunately no one else paid attention to,” said Ron Fournier, a national political writer for the Associated Press in 2000. “The next great presidential candidate—and the next great president—will look a lot like the ‘Straight Talk Express.’”